At this point in the project, most of the sensors were finally in place.

That included:

- Brake disc temperature sensors

- Tyre temperature sensors

- GPS data from the rear section

- Suspension movement using ultrasonic ranging

- Engine coolant temperature

- Input sensing from the front brake, rear brake, and headlight switch

With all of that hardware installed and communicating, it was finally time to answer a simple question:

What does the data actually look like when you ride the bike?

How the system was powered and networked

Before getting into the data itself, it’s important to explain how everything was running during the test ride, because this setup played a big role in how stable the system turned out to be.

All sensor modules were powered from a single 5V power rail, supplied by a separate power bank. This was a deliberate design choice. I wanted the entire sensing and logging system to be electrically isolated from the bike’s main electrical system.

That isolation had a few advantages:

- No risk of interfering with the bike’s ECU or wiring

- Reduced electrical noise from the bike

- Easier debugging when something went wrong

Once the power bank was switched on, all sensor modules booted automatically.

Because the system was fully wireless:

- My phone acted as a WiFi hotspot

- The phone was also running the data logging engine

- All sensor modules connected directly to the phone

This effectively turned the phone into the central hub of the system, handling networking, data collection, and storage at the same time.

In practice, this setup worked surprisingly well. All sensors were within range of the phone, and I never experienced WiFi dropouts during the ride. Every module stayed connected and streamed data continuously.

Looking back, isolating power and keeping networking simple probably saved me from a lot of intermittent and hard-to-debug problems.

The first real data logging run

The first test run itself wasn’t anything extreme. It was simply a ride from home to my workplace under normal riding conditions.

At the time, I wasn’t entirely sure how I would handle the data once it came in. I had already written multiple versions of a Python-based logging engine, and the earlier versions stored data in CSV format.

That’s what I used for the first run.

The ride went smoothly. The sensors logged. The system didn’t crash.

Then I opened the data file.

Realizing the data was too large to handle locally

The CSV file was massive.

There was no realistic way to:

- Scroll through it comfortably

- Inspect it manually

- Make sense of it directly on my laptop

That’s when I started thinking about moving the analysis somewhere with more computing power.

The obvious answer was the cloud.

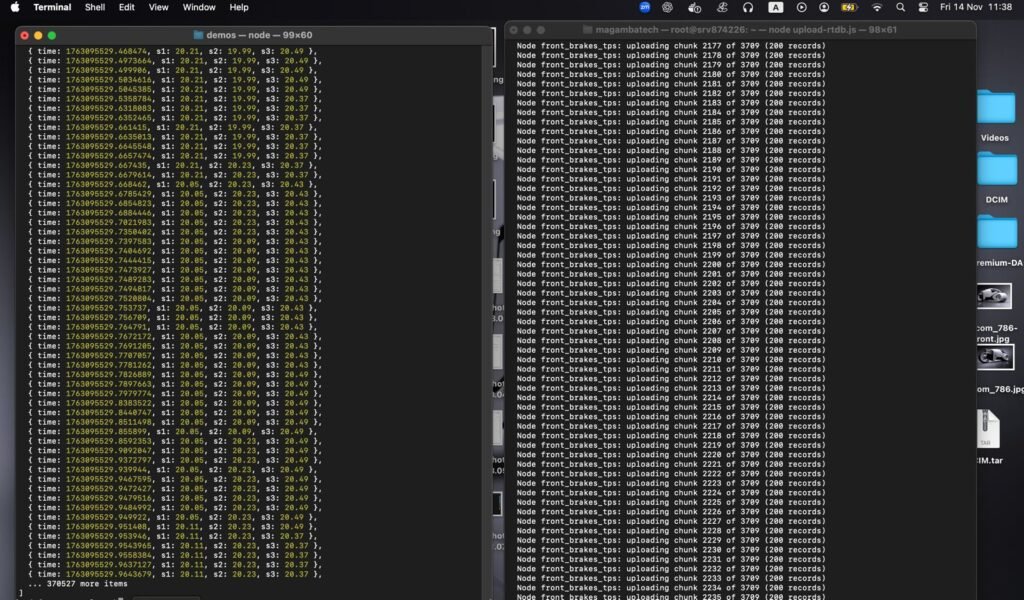

A quick and messy data pipeline (that still worked)

The workflow I came up with wasn’t elegant, but it got the job done:

- Convert the CSV data into JSON

- Upload the converted data to Firebase

- Load the data into Google Colab

- Explore and visualize it using Python

I honestly don’t remember why Firebase was the first thing that came to mind, but it worked.

The downside was obvious:

- Conversion took time

- Uploading the large dataset was slow

- The workflow felt fragile and unsustainable

Still, once the data was available in Google Colab, I could start exploring.

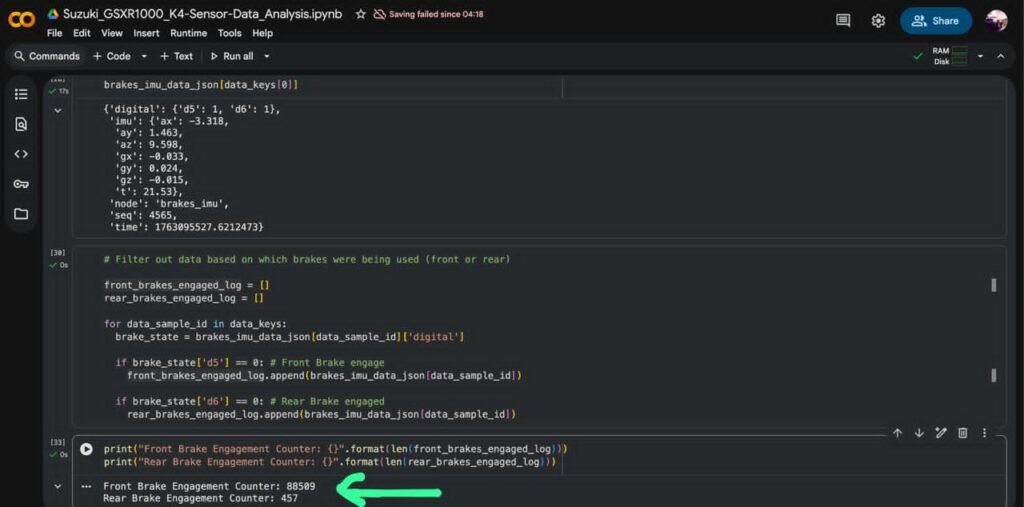

Seeing the data for the first time

This was the moment where everything started to feel real.

Inside Google Colab, I loaded the dataset and began plotting different signals:

- Brake disc temperature over time

- Suspension movement during braking

- Responses during acceleration

- General trends across the ride

Nothing fancy—mostly basic plotting using pandas and matplotlib, tools I had only lightly touched back in college.

But seeing data generated by hardware I built, from a bike I rode, plotted in front of me was incredibly satisfying.

Discovering a major flaw: time synchronization

As exciting as it was, something didn’t look right.

I noticed that:

- Different sensors produced different numbers of data frames

- Some data streams were much denser than others

- Events didn’t line up cleanly across sensors

Up until this point, I had made a bad assumption.

I assumed that because all sensor modules booted at roughly the same time, their data would naturally be synchronized.

That wasn’t true.

Some modules:

- Ran faster loops

- Had more processing overhead

- Sent data at different rates

There was no shared clock.

Rethinking the logging approach

This forced me to rethink how the logging engine worked.

Two ideas came up:

Time-slot based logging

Instead of logging whenever data arrived, I could:

- Define a fixed time window (for example, once per second)

- Sample the latest values from all sensors

- Store them together as a single frame

This would force alignment.

Switching to JSONL

Instead of CSV → JSON conversion, I could:

- Log directly as JSON Lines (JSONL)

- Append one structured record per time slot

- Upload a single file

- Load it directly into Google Colab

We tried this approach—and it worked far better.

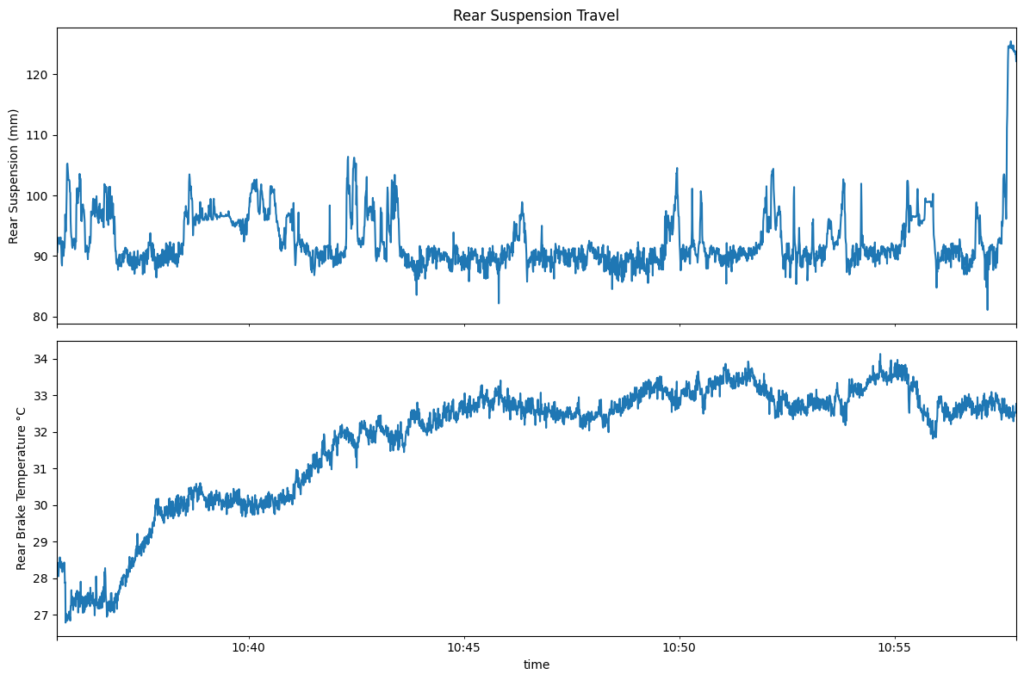

When everything finally lined up

Once the data was time-aligned, everything clicked.

Now I could clearly see:

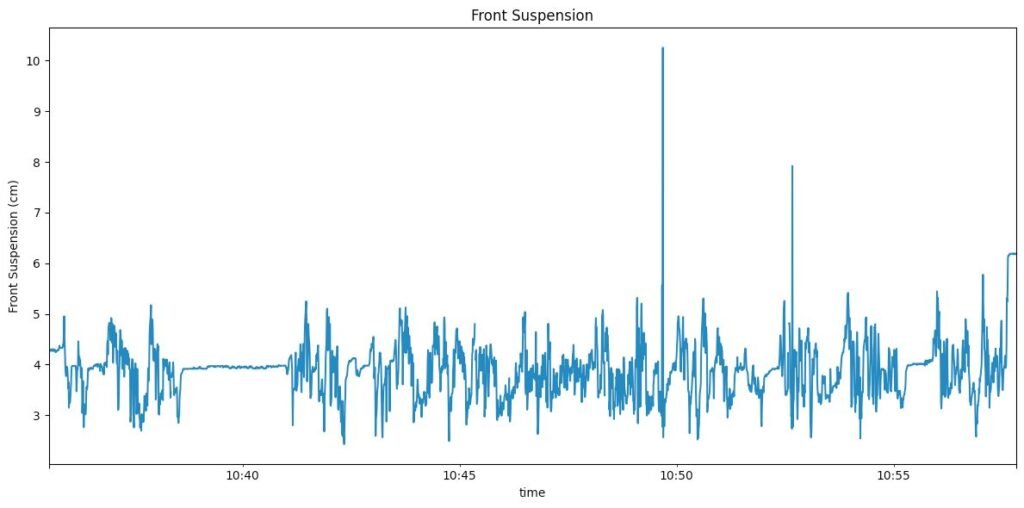

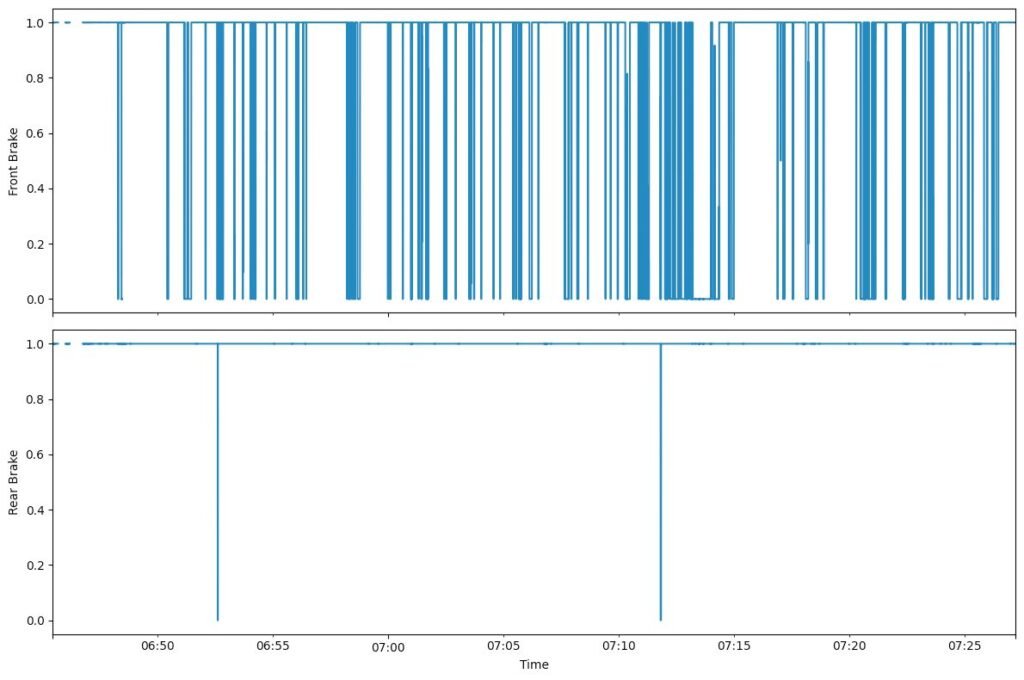

- Brake input events

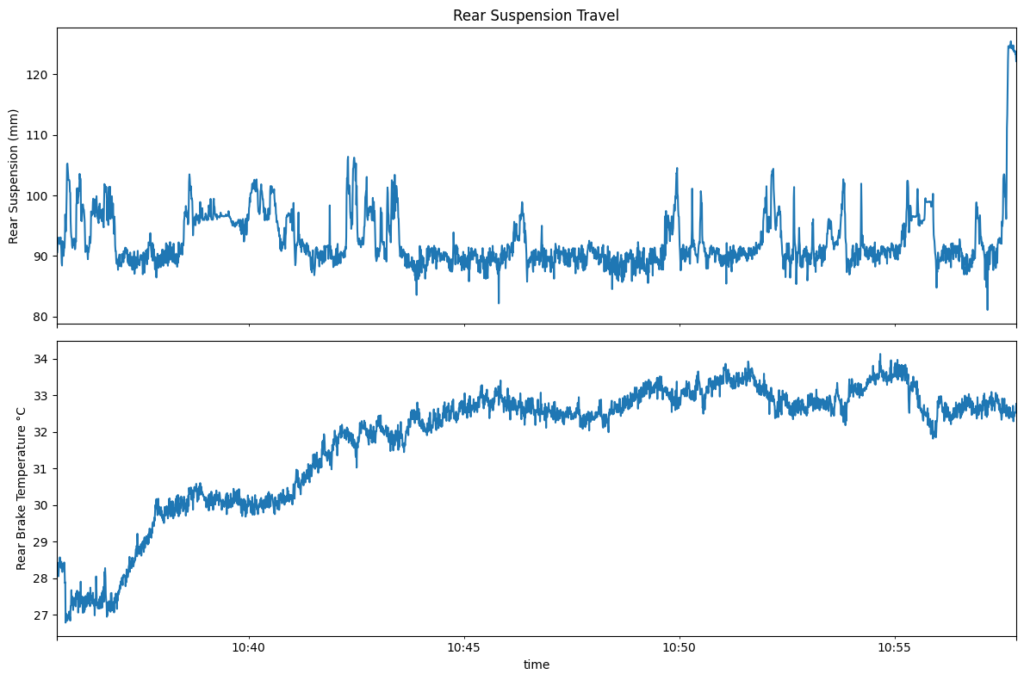

- Immediate suspension response

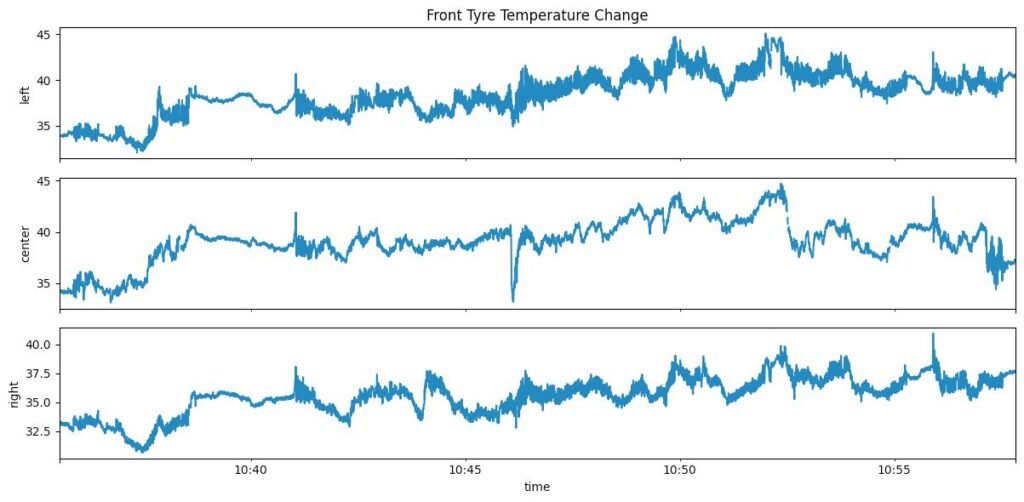

- Brake disc temperature rising

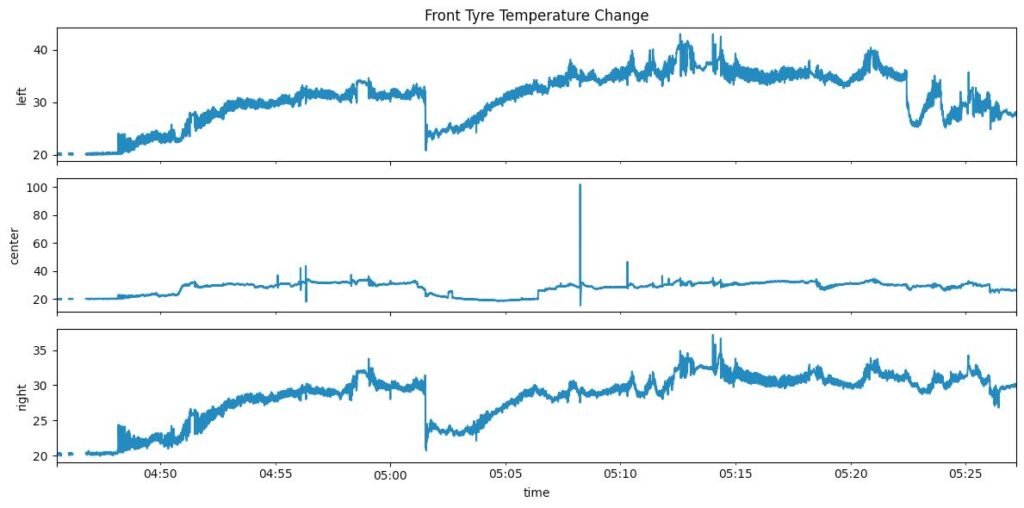

- Tyre temperature reacting more slowly

I could brake hard and watch the system respond:

- Brake signal toggled

- Suspension compressed

- Brake disc temperature climbed

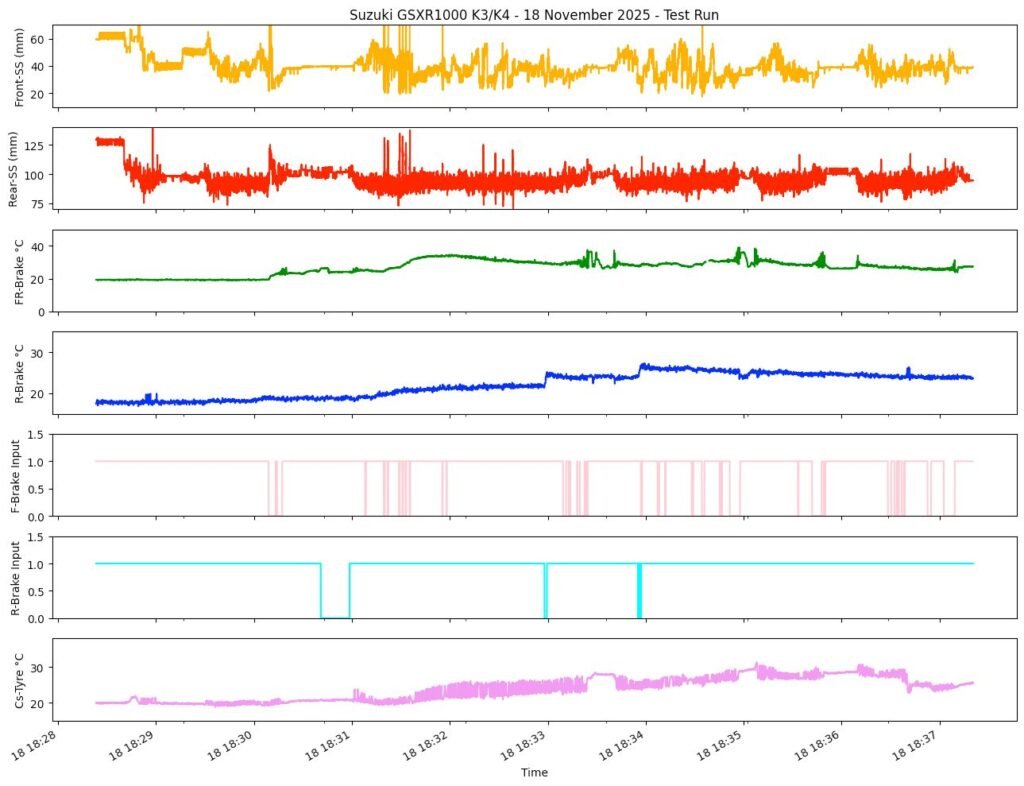

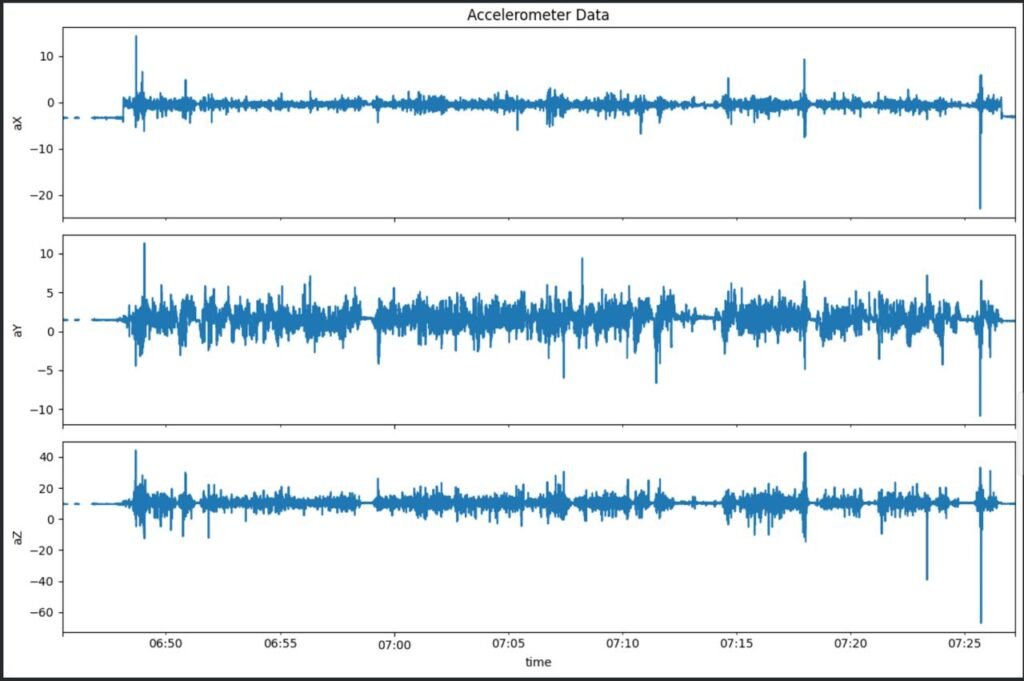

These are some the plots from when I was looking at the data in segments like I could plot the temperature data or IMU data. There is also a brake input plot which are just binary , 1 for when the brake is not engaged and 0 for when the brake is engaged.

Learning the limits of the data

One thing became clear quickly: some runs were simply too short.

Tyre temperature, in particular, doesn’t change much unless:

- You ride longer

- You push harder

- You sustain load

That was fine. This wasn’t about perfect results. It was about understanding what mattered and what didn’t.

This test run was a turning point.

For the first time, the entire loop worked:

- Hardware → data logging

- Data logging → cloud analysis

- Analysis → insight

Even with a messy pipeline and imperfect sensors, the system worked.

I could build hardware, ride the bike, record data, and understand what was happening.

That alone made the project feel worth it.