This part of the project didn’t “work” in the way I originally expected. I wasn’t able to extract clean, stable orientation or lean angle data from the IMUs.

One of the things I’ve always found fascinating about modern super-bikes is how deeply they rely on spatial sensing.

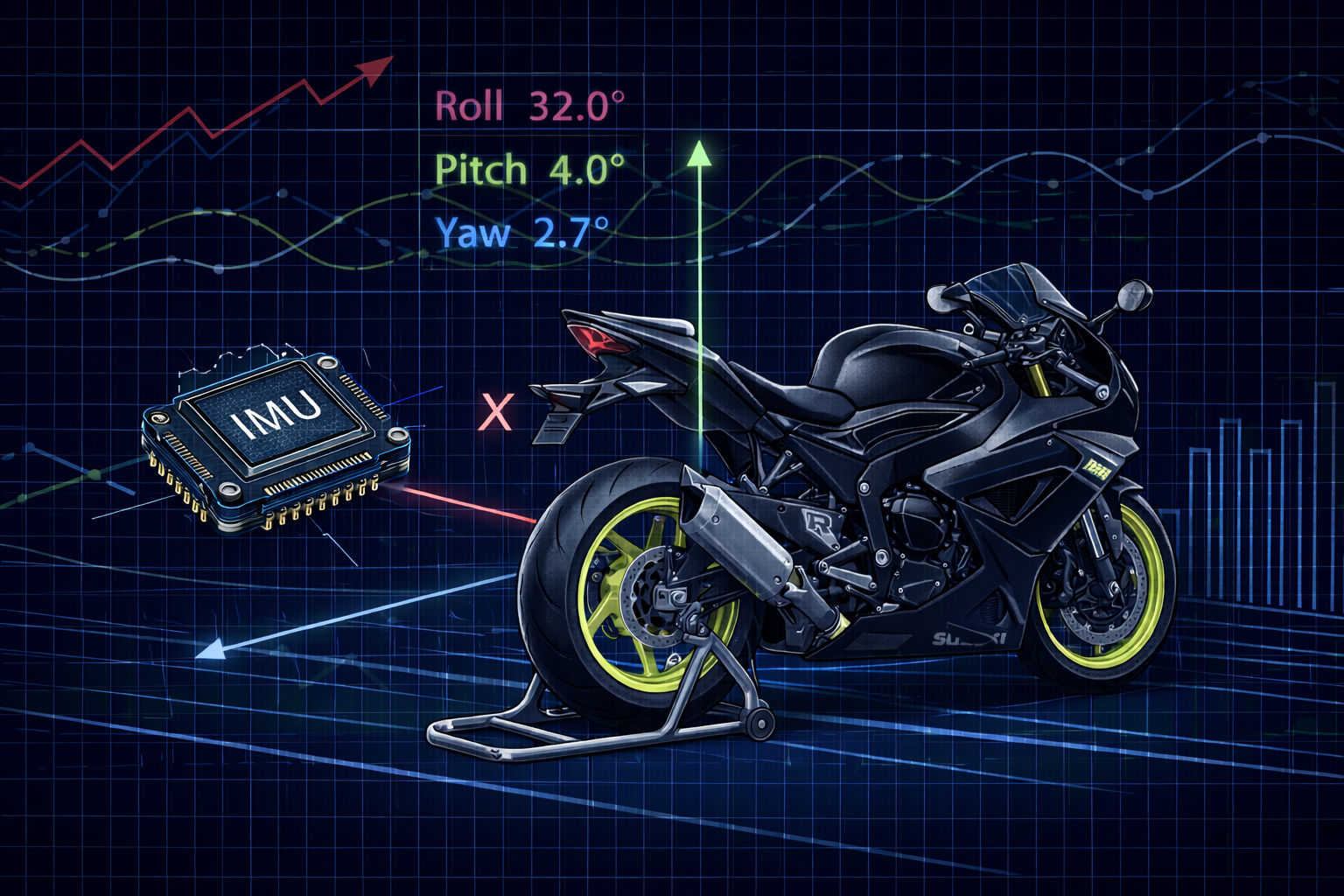

Today, bikes come equipped with IMUs (Inertial Measurement Units) that continuously measure how the bike is accelerating and rotating in three-dimensional space. This data is what enables systems like traction control, wheelie control, and cornering ABS to work the way they do.

On bikes like the BMW S1000RR, Yamaha R1M, or Ducati V4R, IMUs are a core part of the electronics stack.

I wanted to explore the same idea—but strictly for logging and observation.

What an IMU actually measures (and what it doesn’t)

An IMU typically contains:

- a 3-axis accelerometer

- a 3-axis gyroscope

- sometimes a magnetometer (not always)

Together, these sensors measure:

- linear acceleration along X, Y, and Z axes

- angular velocity (rotation rate) around X, Y, and Z axes

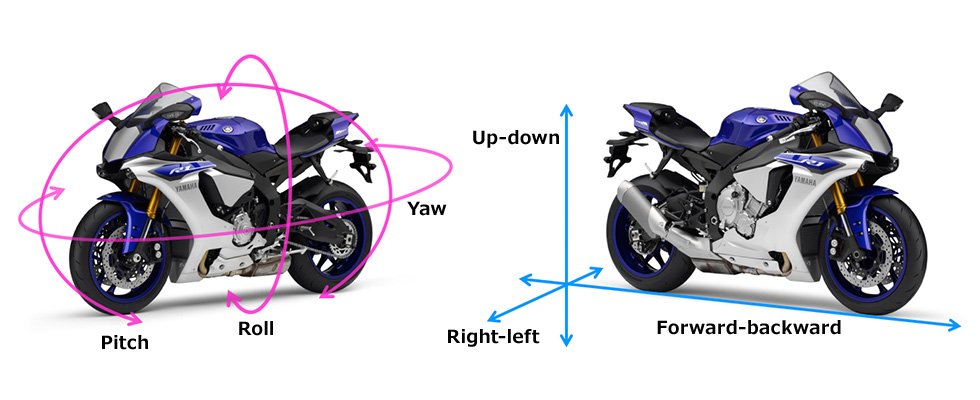

What an IMU does not directly measure is:

- absolute orientation

- lean angle

- pitch or yaw as stable angles

Those values must be computed from raw sensor data using math and filtering.

This distinction turned out to be very important.

My initial IMU plan

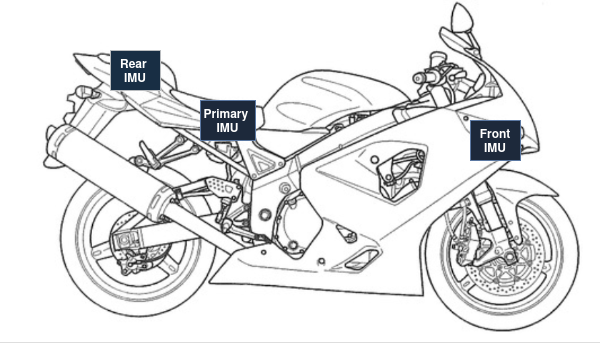

My original idea was to place multiple IMUs across the bike to see how different sections experience motion.

The plan was:

- one IMU in the front section

- one IMU in the mid section

- one IMU in the rear section

Each IMU would:

- have its own microcontroller

- stream data wirelessly to the logging system

The goal wasn’t sensor fusion between IMUs—it was comparison and observation.

Hardware choice: MPU6050 (and why)

I used the MPU6050 IMU module.

This wasn’t because it was ideal, but because:

- it was available

- it’s cheap

- it’s widely documented

- it integrates easily over I²C

The MPU6050 includes:

- a 3-axis accelerometer

- a 3-axis gyroscope

- no magnetometer

That last point matters a lot.

How the IMUs were distributed

To reduce controller sprawl, IMUs were grouped logically:

- Front section:

- one MPU6050

- shared controller with the front suspension ultrasonic sensor

- Mid section:

- two MPU6050 sensors on one controller

- added mainly for redundancy and comparison

- Rear section:

- one MPU6050

- integrated into the rear brake input module

This wasn’t perfect architecture, but it kept controller count manageable and wiring tidy.

First reality check: raw IMU data is not orientation

After test runs, I quickly realized I had misunderstood something fundamental.

I initially assumed that an IMU like the MPU6050 could directly give me:

- lean angle

- pitch

- roll

That’s not how it works.

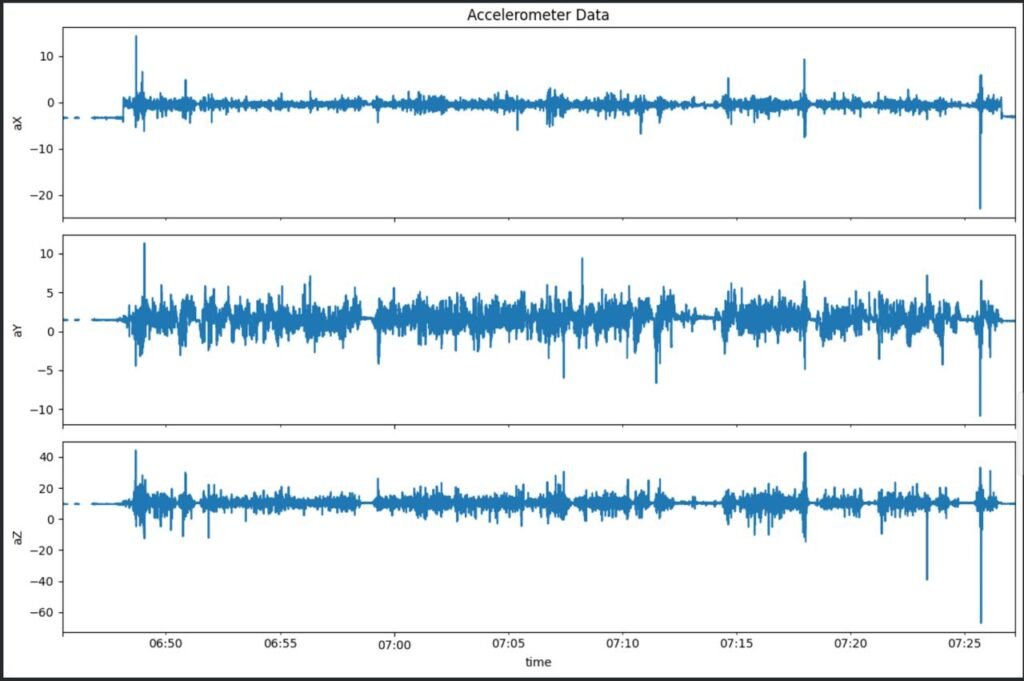

Accelerometer data

The accelerometer measures specific force, not orientation. At rest, this appears as approximately ±1g depending on axis orientation. During motion, acceleration from braking, bumps, and vibration completely dominates gravity.

You can multiply the normalized readings by g to get acceleration in m/s², but that doesn’t magically give orientation.

Gyroscope data

The gyroscope measures angular velocity, not angle. To get orientation, you must integrate angular velocity over time—and integration drifts.

Without correction, drift grows quickly.

Why orientation estimation is hard

To compute stable orientation (roll, pitch, yaw), you need:

- gyroscope integration (fast, but drifts)

- accelerometer reference (noisy during motion)

- magnetometer reference (for yaw correction)

The MPU6050 lacks a magnetometer, which means:

- yaw cannot be stabilized

- long-term orientation drifts are unavoidable

This is why OEM IMUs:

- are carefully calibrated

- use high-grade sensors

- rely on sophisticated sensor fusion algorithms

Mounting matters more than expected

Another thing that became obvious very quickly: IMU mounting is critical.

Poor mounting leads to:

- vibration-induced noise

- resonance artifacts

- axis misalignment

Even small flex or movement in the mount can dominate the signal. This made it very difficult to extract meaningful insight from raw data.

At this stage, the IMUs were doing what they were supposed to do—but interpreting the data meaningfully was a different problem entirely.

Trying lean angle using Android’s Rotation Vector

To get something usable, I experimented with lean angle estimation using the Android Rotation Vector sensor.

Important clarification:

- The Android Rotation Vector is not a physical sensor

- It is a virtual sensor created by sensor fusion

- It combines:

- accelerometer

- gyroscope

- magnetometer (on the phone)

When the bike was stationary, this worked reasonably well. Lean angle readings looked correct.

But once the bike was in motion—especially at higher speeds—the readings became wildly inaccurate. Lean angle would drift by tens of degrees.

Why the Android sensor drifts so badly on a bike

This wasn’t a bug. It was a design limitation.

Android’s sensor fusion algorithms are designed for:

- phones in pockets

- phones in hands

- walking, running, casual movement

They are not designed for:

- high vibration

- sustained acceleration

- aggressive rotation

- a device rigidly mounted to a motorcycle at speed

At high speeds, accelerometer data is dominated by dynamic forces, confusing the gravity reference. The fusion algorithm loses its frame of reference and orientation drifts badly.

This made it clear why OEM systems do not rely on general-purpose phone sensors.

What I learned from the IMU experiments

Even though the data was noisy and hard to interpret, this experiment was extremely valuable.

I learned that:

- IMUs do not give angles “for free”

- orientation requires careful fusion and filtering

- sensor grade matters

- mounting quality matters

- math matters a lot

It also gave me a new appreciation for how complex systems like traction control really are. They don’t just “read lean angle”—they estimate it under brutal conditions.

Why I kept the IMUs anyway

Despite the limitations, I kept the IMU data.

Why?

- relative motion trends were still visible

- spikes during braking and acceleration were clear

- vibration signatures were interesting

- it exposed the real challenges of spatial sensing

Even noisy data can teach you something—especially when you understand why it’s noisy.

What I learnt from this

Implementing spatial sensing—even just for logging—forced me to confront:

- sensor physics

- signal processing

- data fusion

- real-world noise

It made it clear why IMU-based intervention systems take years of development and testing.