After getting a few sensors working individually, it became clear that I couldn’t keep treating them as isolated experiments. If this project was going to grow beyond a handful of wires and test scripts, I needed some kind of system architecture—something that would bring order, make debugging easier, and allow me to add more sensors without everything turning into a mess.

At this point, the goal wasn’t elegance or OEM-level design. It was structure and scalability, even if the hardware itself was still very prototype-grade.

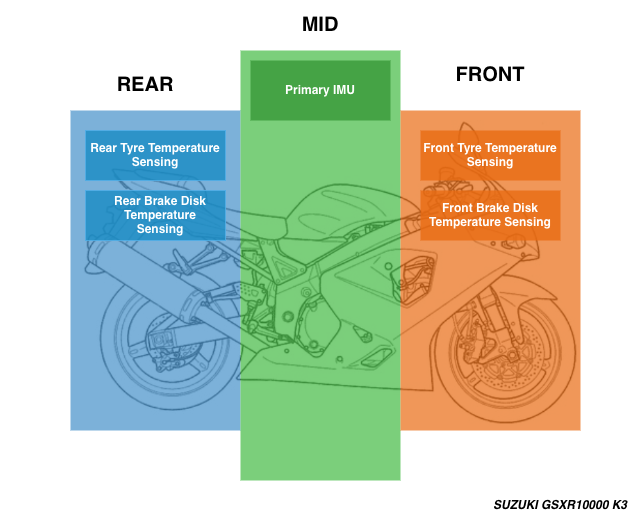

Breaking the bike into logical zones

The first decision I made was to stop thinking about the bike as one big system and instead break it down into three physical sections:

- Rear section

- Mid section

- Front section

This immediately simplified how I thought about sensors, wiring, and future expansion.

Rear section

The rear section already had a few components in place:

- Rear tire temperature sensors

- Rear brake disc temperature sensor

I also knew this area would likely grow later, so I wanted the architecture to allow additional sensors without major changes.

Each rear module was treated as its own unit, responsible only for collecting data and sending it out wirelessly.

Mid section

The mid section was where I planned to add spatial awareness.

The idea here was a simple IMU unit consisting of:

- One ESP8266 microcontroller

- Two MPU6050 IMU sensors

This wasn’t high-end hardware by any means. Everything I was using at this stage was prototype-level, hobbyist gear. But that was fine. The point was to understand the problems first before worrying about precision or robustness.

This mid-section IMU would eventually help describe how the bike was moving, leaning, and accelerating in space.

Front section

The front section already had working modules:

- Front tire temperature sensors

- Front brake disc temperature sensors

Just like the rear, this section was designed with future expansion in mind. The important part was that each module behaved consistently, regardless of where it lived on the bike.

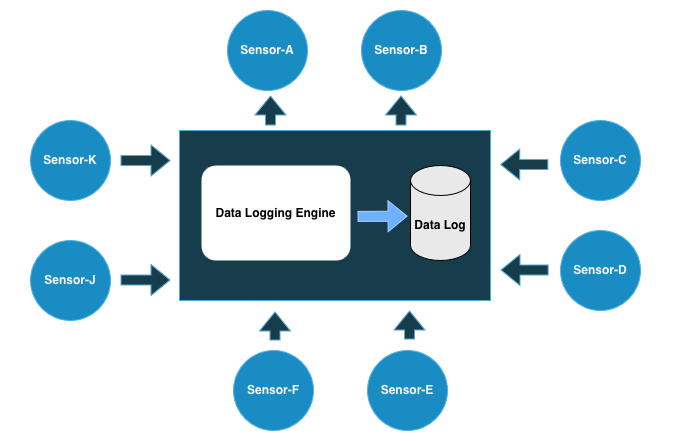

A wireless-first approach

One design choice that stayed consistent across all sections was wireless communication.

Every sensor module sent its data wirelessly to a central data logging system. This immediately removed a lot of complexity:

- No long signal wires running across the bike

- No shared buses stretched through noisy environments

- Easier isolation and debugging

Each module focused on one job:

- Read sensors

- Package data

- Transmit it

Everything else happened elsewhere.

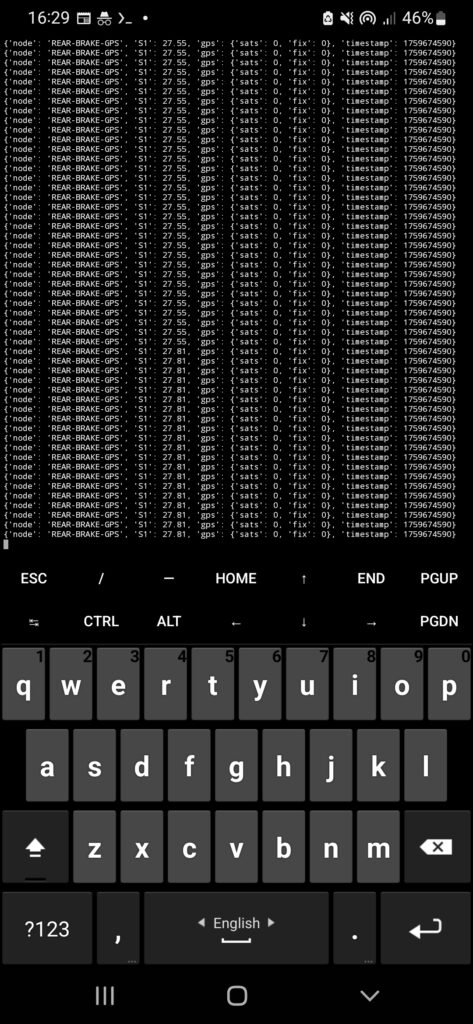

First full system power-up

The first time I powered everything on together was genuinely interesting. Data started flowing in from multiple places on the bike, all at once.

At that moment, the system worked—but it also raised new questions.

The biggest one was data storage.

Deciding how to store the data

Each sensor module was already sending its readings in JSON format. That made debugging easy and human-readable, but it also made me think about performance.

Looking back, JSON may not have been the most efficient choice:

- It’s text-based

- It involves string operations

- It’s slower than raw binary formats

But at the time, usability mattered more than speed.

I hadn’t yet decided whether the final data logs would be:

- CSV files

- JSON files

- Or something else entirely

The key requirement was that the data had to be easy to analyze later using Jupyter Notebook or Google Colab. That decision would shape everything downstream, and it’s something I’ll cover in a separate article.

Early data logging and debugging

Before building a single “master” logging engine, I took a more pragmatic approach.

I wrote small Python programs that:

- Listened on specific UDP ports

- Received data from individual sensor modules

- Printed or stored the incoming data

Each module sent its data to a dedicated port, which made debugging much easier. If something looked wrong, I could isolate that one stream without guessing.

The long-term plan was always to replace this with:

- A central data logging engine

- Multiple threads, each handling a module

- A system that flattened all incoming data into a unified structure

But for early development, simple tools were enough.

Powering the system (on purpose, not accidentally)

One design decision I was very deliberate about was power isolation.

All sensor modules were powered from a single 5V rail, supplied by an external power bank. I could have used a 12V-to-5V converter and tied everything into the bike’s electrical system, but I chose not to.

The reason was simple:

- I didn’t want experimental electronics touching the bike’s primary electrical system

- I wanted failures to be contained

- I wanted to debug without risking the bike itself

This separation gave me peace of mind while experimenting.

What this stage taught me

Designing the system architecture didn’t magically make everything easy, but it did make the complexity manageable.

A few things became clear:

- Thinking in zones simplifies physical design

- Treating each sensor as an independent module scales well

- Early architecture matters, even for hobby projects

- Debugging is much easier when data streams are isolated

This stage wasn’t about perfection. It was about creating a foundation solid enough to build on—and fragile enough to teach me where the real problems were.