By the time I had several sensors working reliably, I started to realize something slightly ironic:

even though I was already capturing a lot of data, I actually needed more parameters.

Not because the project wasn’t complex enough already—but because the data I had didn’t always explain why things were happening.

That realization pushed me to focus more heavily on the rear section of the bike.

Why the rear section became the focus

The rear section made sense as a place to expand for a few reasons:

- There was physical space to mount additional electronics

- It already hosted temperature sensors

- It was a logical place to integrate GPS and brake-related data

- It could act as a “hub” for several related measurements

Instead of scattering more single-purpose modules everywhere, I wanted to experiment with grouping functionality.

Designing a more modular rear electronics unit

The first new rear module I planned needed to do several things:

- Monitor rear brake disc temperature

- Integrate a GPS module

- Allow for future expansion (including a possible speed sensor)

- Be detachable and reprogrammable

- Use connectors rather than hard-wired connections

In my head, this module started to resemble a very crude version of an ECU-style unit—not in function, but in philosophy. Something you could unplug, reflash, and reinstall without disturbing the rest of the system.

Adding brake signal monitoring

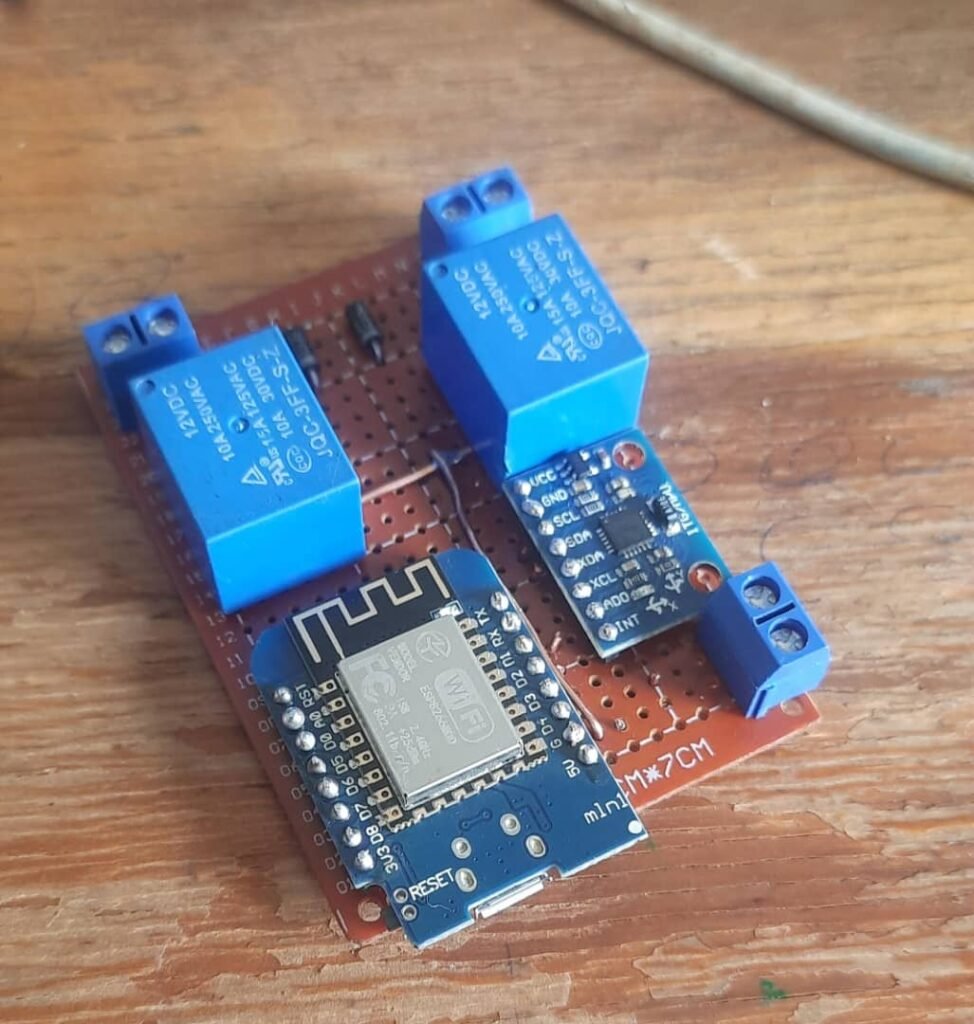

The second rear module focused on brake signal monitoring.

What I wanted here was simple but important:

- Detect front brake activation

- Detect rear brake activation

This module used:

- An ESP8266 controller

- Two 12V relays connected to the brake light circuits

- Logic-level outputs (1 or 0)

There was no brake pressure sensing, no analog finesse—just a clean digital signal telling me when braking occurred.

That alone was extremely valuable.

By having brake inputs, I could now correlate:

- Braking events

- Suspension dive

- Brake disc temperature rise

- Tyre temperature changes

Adding an IMU to the rear section

While working on the brake signal module, I also decided to integrate an MPU6050 IMU into the rear section.

The idea was to:

- Capture motion data closer to the rear of the bike

- Compare it with IMU data from the front or mid section

- See how different parts of the bike experience movement differently

This wasn’t about sensor fusion yet—it was about observing differences.

GPS integration (simple, but useful)

For GPS, I kept things intentionally basic.

I used a u-blox NEO-6M GPS module, which is:

- Cheap

- Widely available

- Easy to integrate

- Relatively slow in refresh rate

I knew upfront that the refresh rate would be limited, so this wasn’t going to give me high-resolution speed or position data. But it still had value:

- Location context

- Rough speed reference

- Time alignment with other data streams

To mount it, I designed a small rear wing that kept the GPS module exposed. It also happened to look kind of cool, which was a bonus.

Keeping communication consistent

Just like the other sensor units, these rear modules:

- Used ESP8266 controllers (Wemos D1 form factor)

- Connected wirelessly to the sensor network

- Sent data to the central logging system

By keeping the communication model consistent, integration was straightforward. New modules could come online without major changes to the rest of the system.

The ESP8266 everywhere problem

At this point, almost everything was using an ESP8266—and that was both good and bad.

On the plus side:

- Small footprint

- Easy to program

- Built-in WiFi

- Cheap and replaceable

On the downside, I started to notice something worrying.

I had:

- A dedicated front brake disc sensor controller

- A dedicated front IMU and suspension controller

- A dedicated engine coolant and pass-light trigger module

- Multiple rear modules

Just in the front section alone, I was already running three separate microcontrollers.

The system was working, but the module count was exploding.

Realizing the need for consolidation

This rear-section experiment taught me an important lesson:

You can make many small, dedicated modules—but complexity grows fast.

In an ideal world, I would have:

- One larger module per section

- Multiple sensor connectors per module

- Fewer microcontrollers

- Cleaner wiring

- More uniform design

But there was a trade-off.

If I stopped to redesign everything properly, I would risk falling into analysis paralysis.