After working through temperature sensing and system architecture, the next area I wanted to explore was suspension behavior.

Modern superbikes equipped with electronic suspension systems—such as dynamically damped suspension—can actively adjust and monitor suspension in real time. My bike doesn’t have any of that. It runs a standard mechanical suspension with no electronics involved.

That didn’t mean the suspension wasn’t doing interesting things. It just meant I couldn’t see them.

So the goal here wasn’t control or tuning. It was observation.

What I wanted to learn from the suspension

I was interested in understanding how the suspension behaves in everyday riding conditions:

- How much does it compress under hard braking?

- What happens during acceleration?

- How does it behave during steady cruising?

- How does rough road surface affect movement?

In short, I wanted to monitor compression and rebound, not intervene or adjust anything.

Why I avoided mechanical measurement

The most direct way to measure suspension travel is with mechanical linkages or linear position sensors. I ruled that out very early.

Mechanical setups:

- Add complexity

- Require precise mounting

- Can interfere with moving parts

- Are fragile in a vibration-heavy environment

I wanted something non-contact, simple, and safe to experiment with.

That’s what led me to ultrasonic distance sensors.

How ultrasonic ranging works (simple explanation)

Ultrasonic ranging is based on a very straightforward idea.

An ultrasonic sensor:

- Emits a short burst of high-frequency sound (ultrasound)

- That sound travels through the air until it hits an object

- The sound reflects back to the sensor

- The sensor measures how long the echo takes to return

Because the speed of sound in air is known, the distance can be estimated using time-of-flight:

Distance = (time × speed of sound) / 2

The division by two accounts for the sound traveling to the object and back.

In this project:

- The sensor was mounted to the bike frame

- The reflecting object was the wheel or tire

- Changes in distance corresponded to suspension movement

As the suspension compresses or extends, the measured distance changes.

Why ultrasonic sensors made sense for this project

Ultrasonic sensors aren’t precision instruments, but they have a few advantages that made them ideal here:

- Completely non-contact

- Cheap and easy to replace

- Simple to interface with microcontrollers

- Fast enough to capture suspension movement trends

Most importantly, they let me observe relative movement, which was the real goal.

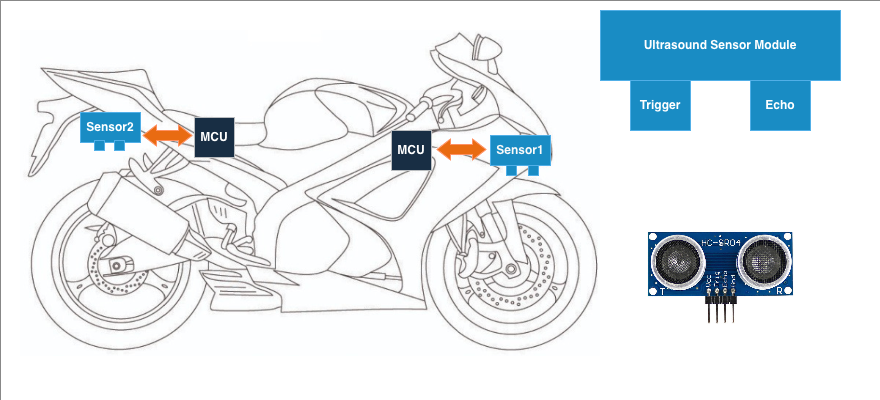

Sensor placement on the bike

I installed:

- One ultrasonic sensor at the rear

- One ultrasonic sensor at the front

Each sensor was positioned so it faced the wheel directly, measuring the gap between the wheel and a fixed point on the bike.

As the suspension moved:

- Compression reduced the distance

- Rebound increased the distance

What surprised me was how quickly this worked. Once mounted and powered, the sensors immediately started reporting meaningful changes.

What I was measuring (and what I wasn’t)

Technically, you can calculate real suspension travel by:

- Recording a baseline distance

- Tracking changes from that baseline

- Converting distance changes into displacement values

I chose not to do that.

Accuracy wasn’t the objective here. I wasn’t aiming for millimeter-perfect measurements or shock dyno data. What I wanted was behavioral insight:

- Relative compression vs extension

- Fast vs slow movement

- Smooth vs chaotic response

Seeing patterns mattered more than absolute numbers.

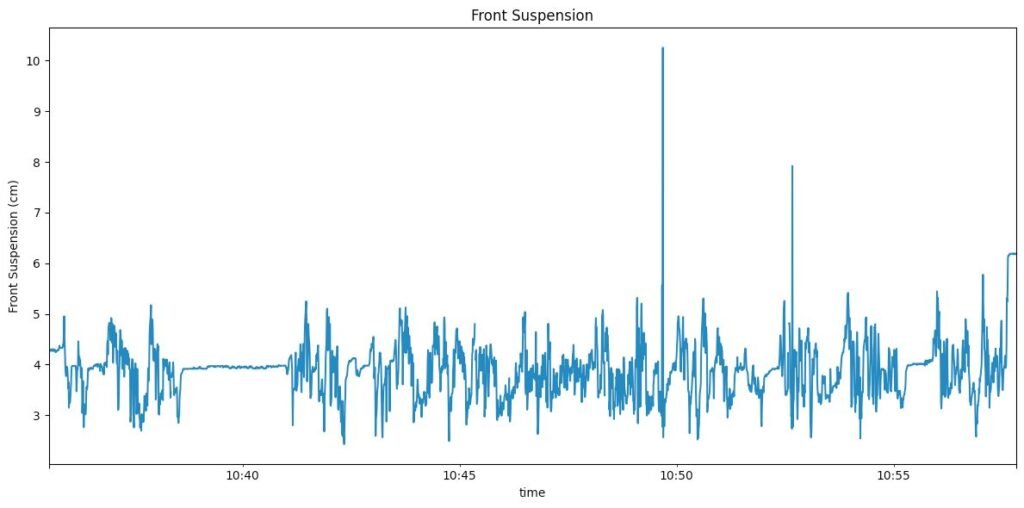

Visualizing suspension movement

Once data started coming in, plotting it made the behaviour obvious:

- Sharp spikes during hard braking

- Gradual compression during acceleration

- Continuous small oscillations on rough roads

Even without exact units, the shape of the data told a clear story.

Considering laser distance sensors

I did consider using laser ranging sensors instead of ultrasonic ones.

Laser sensors offer:

- Higher precision

- Faster response

- More focused measurement beams

But they’re also much more expensive. For a learning-focused, experimental setup, ultrasonic sensors struck the right balance.

Dealing with jitter and noisy data

One of the first issues I ran into was jitter.

The distance readings fluctuated significantly because:

- The sensors updated very frequently (milliseconds)

- The environment was mechanically noisy

- The wheel surface wasn’t perfectly uniform

This wasn’t a hardware problem—it was a data problem.

Simple filtering on the software side helped smooth the signal and made the suspension behaviour much easier to interpret.

What this experiment taught me

Using ultrasonic sensors to monitor suspension movement wasn’t perfect, but it was extremely informative.

Key takeaways:

- You don’t need high accuracy to gain insight

- Non-contact sensing simplifies experimentation

- Relative measurements are often enough

- Simple sensors can reveal complex behaviour