I started building sensors and see what would actually work on a real motorcycle. This part of the project involved a lot of fabrication, testing, programming, and trial-and-error. It was also where my assumptions about “simple sensors” started to break down.

I didn’t start with the most complex system. I picked something that felt measurable, visual, and useful: tire temperature.

Starting with rear tire temperature

The first module I worked on was the rear tire temperature unit. The idea was straightforward. I wanted to measure the temperature of the tire across three regions:

- Left edge of the tire

- Center of the tire

- Right edge of the tire

To do this, I used three non-contact infrared temperature sensors (MLX90614). The plan was to connect all three sensors to a single microcontroller, read their values continuously, and stream the data back wirelessly.

At this stage, the goal wasn’t perfect accuracy. It was to answer a much simpler question:

Can I even collect usable temperature data from a moving motorcycle tire?

Choosing WiFi over wiring

One of the early design decisions was how these sensor modules would communicate. Running wires back to a central unit would have meant implementing a proper communication bus, something like CAN. That would have required extra hardware, more complexity, and more cost per module.

SPI or I2C over long runs also didn’t feel like a good idea. Those protocols are sensitive to noise and interference, especially in an environment full of vibration, heat, and electrical noise.

So I went with WiFi.

I was using an ESP8266-based NodeMCU, which already had WiFi built in. It wasn’t the most elegant solution, but it was available, cheap, and flexible. Each sensor module could be self-contained and transmit data independently.

Sending data with UDP broadcast

To keep things simple, I chose UDP for data transmission. Unlike TCP, UDP is connectionless, which meant I didn’t have to manage connections, retries, or handshakes. If a packet was lost, that was fine—I cared more about trends than perfect delivery.

I also decided to broadcast the data packets over the local network instead of sending them to a fixed IP address. That way, I didn’t have to hardcode destinations into the modules. Any listening program could receive the data.

To test this, I wrote a small Python script and also used tools like ncat to listen on the network. Seeing raw temperature values coming in over the network for the first time was genuinely exciting. It meant the concept worked.

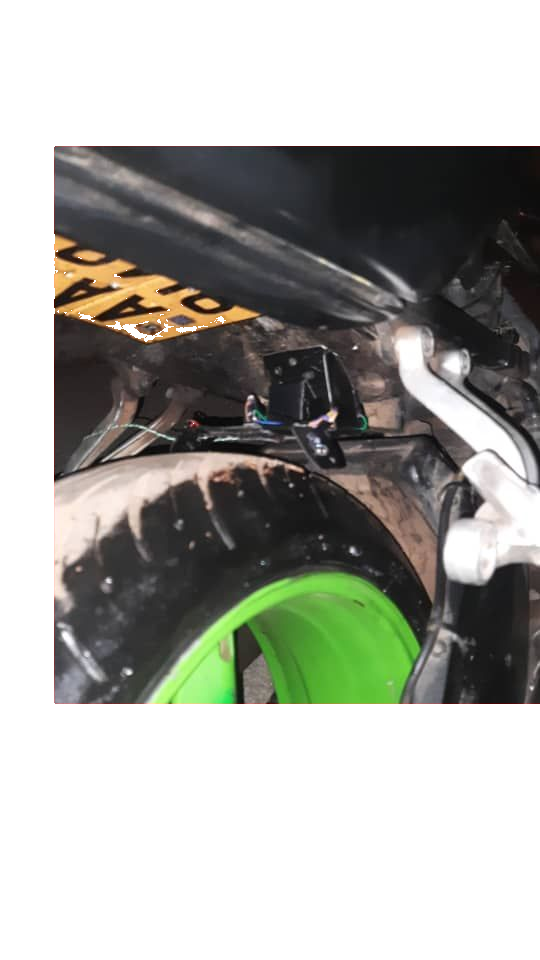

Mounting challenges on the rear

Once the rear module was working electrically, I ran into a very physical problem: placement.

The bike didn’t have a rear tire hugger, which would have been ideal because the sensor could move with the wheel and maintain a consistent distance. Instead, I ended up mounting the module on the tail section, close to the tire.

It wasn’t perfect, but it was good enough for a first test. The module stayed in place, the sensors read values, and data continued streaming over WiFi. That was enough to move on.

Front tire temperature module

The front tire temperature module followed a similar design: three infrared sensors measuring left, center, and right sections of the tire. This time, mounting was easier because the bike had a front tire hugger. That allowed for a more stable and consistent setup.

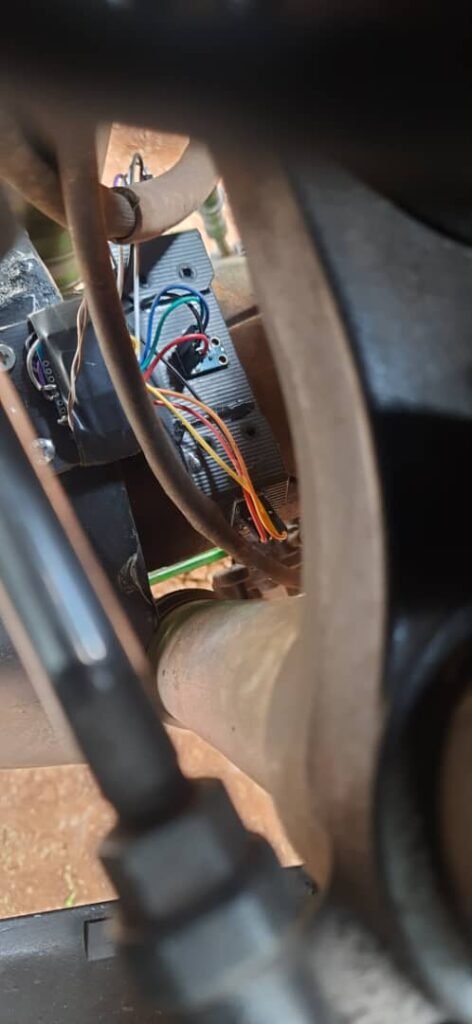

Electrically, though, this is where things started getting tricky.

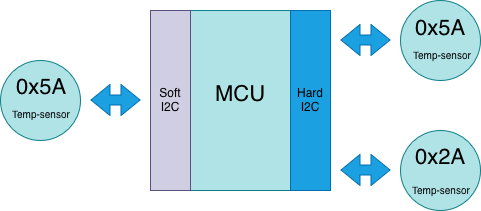

The I2C address problem

The MLX90614 sensors communicate over I2C. Normally that’s not an issue, but these sensors come in different variants with fixed I2C addresses. Most of the sensors I had used the same default address (0x5A). If you try to put multiple devices with the same address on a single I2C bus, it simply doesn’t work.

Out of the batch I had, only two sensors used a different address (0x2A). But I needed three sensors per module.

The workaround was a bit of a hack.

I placed two sensors—one with address 0x5A and one with 0x2A—on the hardware I2C bus of the ESP8266. For the third sensor, I implemented a software I2C bus on different GPIO pins using a library.

This meant:

- Two sensors on the hardware I2C bus

- One sensor on a separate, software-emulated I2C bus

It wasn’t elegant, but it worked.

Multiple modules, multiple data streams

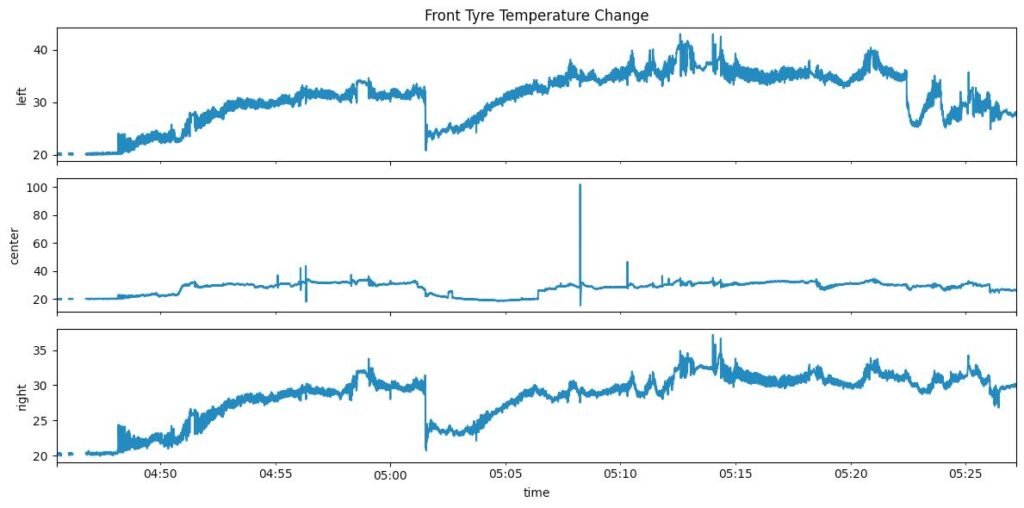

This is test run data plot of the front tyre and you can the temperature of the left-edge ,center and right edge section of the front tyre. I will explain in brief what was happening when this test drive happened. Basically when we started at 0450am to around 0500 the temperature the edges rises and then we see a sharp drop as this was a traffic stop and then it starts to rise again as we continue flactuating. What was interesting was how the edges got warmer than the center and this was a normal work commute not a track run.

With both the rear and front tire temperature modules working, I configured each module to transmit data on a different UDP port. This made it easier to route and process the data on the receiving side without mixing streams.

At this point, I had:

- A rear tire temperature module sending data

- A front tire temperature module sending data

- Both broadcasting over WiFi using UDP

- Real temperature readings coming in from a moving motorcycle

This was the first moment where the project felt real.

What this stage taught me

Building these first sensor modules taught me a few things very quickly:

- Hardware constraints show up fast in the real world

- “Simple” protocols like I2C can become limiting

- Wireless communication simplifies wiring but introduces its own trade-offs

- Physical mounting is just as important as electronics

Most importantly, it showed me that collecting data was possible—but also that every new sensor would come with its own set of problems.